Smithsonian Castle

Welcome to Design Spotlight, a monthly blog post that delves into the design of Washington’s architectural marvels and best kept secrets! Read along for an insider’s look at the conflicts, controversies, and personalities that have shaped our Capital City. This month, we’ll explore the Smithsonian Institution Building, better known as the Smithsonian Castle.

In our last Design Spotlight, we featured the story of James Smithson, the British chemist and minerologist for whom the Smithsonian Institution is named. Though no one knows what inspired his gift, Smithson left his entire fortune “to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.”

Incredibly, Smithson never came to the United States in his lifetime, but his legacy lives on in the Smithsonian’s 20+ museums, galleries, and research centers across the globe. Along with the Nation’s greatest leaders, Smithson also has a well-deserved, and distinctively unique, “monument” on the National Mall: the Smithsonian Castle.

The Contest to Build the Smithsonian Institution

After settling Smithson’s estate and bringing his effects to the United States, an act of Congress established the Smithsonian Institution as “a museum, scientific research laboratories, an observatory, and a library and copyright depository” in 1846. Naturally, this new institution needed a place to live. Like most of the National Mall’s other famous buildings and memorials, the designer of the new Smithsonian Institution was chosen by the most egalitarian, American means possible: a contest.

This competition attracted the Nation’s most noted architects, including John Notman and Robert Mills, designer of the Washington Monument. However, in the end, the selection committee unanimously chose the design of a lesser known, up-and-coming architect, James Renwick Jr.

Born in 1818 to a prominent New York family, Renwick was not a formally trained architect. Renwick gained his passion for architecture and design through the travel and education that his well-to-do background afforded him. At the ripe age of 12, he entered Columbia University to study engineering and graduated in 1836. Three years later, he earned his master’s from Columbia and began working as a structural engineer for the Erie Railroad. It wasn’t until he won the design competition for Grace Episcopal Church in New York in 1843 that Renwick became a practicing architect.

Renwick would later go on to design many noteworthy buildings, including St. Patrick’s Cathedral in his native New York City, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art (now known as the Renwick Gallery) in Washington DC. But amazingly, the Smithsonian Castle was only his second commission as an architect.

Bringing Old World Style to the New World

At the request of the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, the new home for the Smithsonian Institution was meant to be designed in a Romanesque style. Incorporating design elements from both Roman and Byzantine style. Key features of Romanesque style are:

-

heavy massing; thick walls; round arches; large, sturdy columns; barrel (rounded) vaults; large towers; decorative arcades (a series of columns and arches)

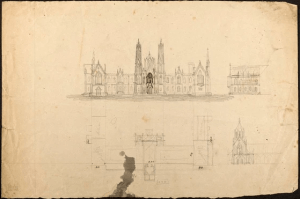

Renwick, who had a deep knowledge of architectural history, wanted the new home of the Smithsonian to reflect the wisdom that the organization would promote. Expanding upon the relative simplicity of Romanesque design, Renwick chose to compose his design in the Gothic Revival style, to echo the aesthetic of European educational institutions like Oxford and Cambridge.

More ornate and intricate than Romanesque, Gothic Revival style includes elements like:

-

rose windows

-

vaulted ceilings

-

tall, thin windows

-

towers

-

steeply peaked roofs

These grandiose, Old World elements helped confer upon the Castle the sense of scholarship and wisdom that both Renwick and the Board of Trustees were seeking.

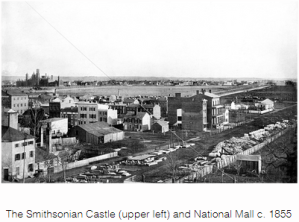

Upon its completion in 1855, the Castle sat mostly isolated at the edge of the National Mall. However, at the turn of the century, as modern Washington began to take shape and the Smithsonian expanded, more buildings were added around it. As the Smithsonian Institution’s collections grew, the Smithsonian Castle would be joined by the Arts and Industries Building (1879), the National Museum of Natural History (1910), and many others. Today the Castle holds a place of honor on the National Mall, its distinct design making it an unmistakable fixture of Washington DC.

Layout of the Castle

Built of sandstone from nearby Seneca, Maryland, the Castle is composed of a central section, two extensions, and two wings. It also has many towers, though only four contain usable space; the others are simply decorative. Originally, Renwick intended for the building to be composed of white marble, but the committee eventually settled on red sandstone, which was quarried locally and easily transported along the C&O Canal to Washington.

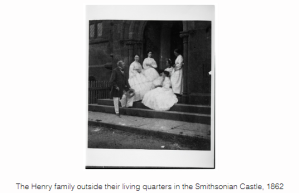

The West Range was used as a reading room, and the West Wing as a library. The far East Wing was designed as living quarters for the Secretary of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry and his family.

A History of Change

Over the years, the Castle has undergone several reconstructions and renovations, partly due to fire. In 1865, a fire destroyed the upper story of the central section, along with the north and south towers. It consumed most of James Smithson’s effects that had been brought over from England after his death. Among other losses, the fire destroyed many works of art, including over 200 paintings by John Mix Stanley; the public libraries of Alexandria, VA and Beaufort, SC (seized by the Union Army during the Civil War), and the papers and living quarters of Joseph Henry.

In 1883, the east wing was enlarged to add more office space, and the castle was fireproofed. Another renovation in the late 1960s restored some of the building’s original Victorian elements than had been changed over the course of 100+ years. Modern fluorescent light fixtures were replaced with the building’s original gas chandeliers—now electrified.

Today’s Smithsonian Castle

Today, the Smithsonian Castle is an unmistakable and irreplaceable landmark on the National Mall. It serves primarily as a visitor center, with interactive exhibits and highlights from each museum on display. While the Institution’s collection may have outgrown its original home, the Smithsonian Castle still serves as a centerpiece, surrounded by the museums it helped establish.

The Castle is also the final resting place of the Smithsonian’s benefactor, James Smithson. Though Smithson never came to the United States in his lifetime, his remains eventually made the journey. Smithson was disinterred from his burial site in Genoa, Italy and brought to the Smithsonian Castle to be permanently memorialized. Visitors can still visit Smithson’s crypt during the Castle’s regular business hours.

Normally this architectural gem can be seen on our Castle to Capitol walking tour, but for the time being, you can safely take a virtual tour of the whole building and enjoy its collections, rich history, and distinct design.